Emma’s Dilemma: We are trashing history

March 10, 2017

I don’t have Snapchat. Or Instagram. Or Facebook or Twitter or any other form of social media. I don’t share my amateur photography with the rest of the world as many do. And frankly, I’m glad of that. Photos are heartbeats captured in a moment’s flash of color and light. It’s a shame we post a picture and send a snap without a second thought as to what history we are recording with each shot we take.

Social media, specifically Snapchat and Instagram, are the primary culprits of photography carelessness. According to omnicoreagency.com, “It would take you 10 years to view all the photos shared on Snapchat in the last hour. By the time you’d viewed those, another 880,000 years’ worth of photos would have been shared.”

What’s disturbing is that the thousands of photos constantly being shared are never fully appreciated. Snaps are only intended to be seen once.

What a shame.

Photos preserve history, and without them we wouldn’t know or recognize many of the world’s most ancient heroes. A Baltimore Sun article headlined “The power of photography” by John Stauffer addresses Frederick Douglass’ photographic portraits and the role they played in society. In his effort to show the world that “he had as much claim to citizenship, with the rights of equality before the law, as his white peers,” Stauffer said, Douglass became “the most photographed American in the 19th century.”

“Nowadays, his portraits serve as an important visual legacy,” Stauffer said. “His face and demeanor broadcast a protest against lynching and segregation.” The faces we see when we hold a photo in our hands tell us stories and lessons that we otherwise wouldn’t be able to recall or learn.

And it’s not just historical figures whose faces trigger memories. Think of your grandparents and great-grandparents, whose faces you can picture though you never met them while they were still alive.

My uncle died in a car accident when he was eighteen. I never heard his laugh, never waved him goodbye, but I still know his face: he had red hair, green eyes, and a smile like my brother’s. If not for the photos scattered about my grandparent’s house, I would not know him at all.

There are easy ways to make sure old faces aren’t forgotten, such as scrapbooking, journaling, and using a Polaroid camera. It’s important that these images are tangible.

On my desk at home is a photo of my dad and me at a church event when I was eleven years old. I was dressed up in a little flowery dress and pearls, and my dad was wearing a bow tie. We posed in a makeshift photo studio, meant to resemble a princess’ castle. I sat in a puffy pink chair with my hands folded in my lap, and my dad stood behind me, his hand resting on my shoulder.

There is only one copy of this photo. I don’t know where it exists digitally, if at all. If I lose that glossy 4×6 card of ink, I will never see it again, and that little snapshot in my history will be gone. That photo – and that memory – means the world to me because it can be lost in one tragic moment. Photos should be fragile. They mean more when they’re easily disposable.

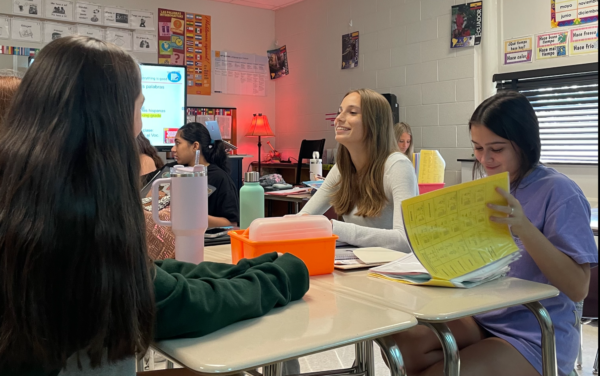

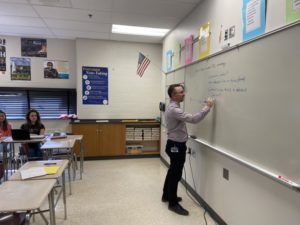

Each little snippet of your Snapchat story is a snippet of your history. Each image you post on Instagram is an instant in your ever-growing past. Each photo I take for the Harbinger captures a moment in Hereford’s legacy. I beg you, don’t be so careless with yours.